EDIBLE TRADITIONS

Dorchester’s Clapp Pear

WORDS BY ELIZABETH GAWTHROP RIELY/ PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL PIAZZA

“Why is this pear here?” the man asked, pointing to a giant pear in the middle of the little park inDorchesterone recent morning. “And why is it brown?”

Although he looked a bit down on his luck and slipped a bottle beneath his jacket lying on the park bench, his questions to the woman were clear and on target. He really wanted to know. The enormous pear sculpture stood there, 12 feet tall, with seating and plants around it in the park where he and his friend “come here from time to time,” as he put it. Next door was a KFC, with Dunkin’ Donuts and the Great Wok across the busy intersection of Five Corners, where Massachusetts Avenue, Columbia Road, Cottage and Boston Streets all come together in an urban stew of asphalt, exhaust fumes and fast-food aromas.

Dorchester used to be farmland and gardens, she told him, before it became a part ofBoston. Fruit grew in orchards all over the neighborhood, and this particular type of pear, Clapp’s Favorite, was grown by a man who lived on a large farm up the street where he had many pear trees. Slowly, gradually, she told him that this pear was made of bronze, and that she was the sculptor who made it.

Seeing that he was still interested, she showed him some of the small sculptures standing on bollards around the giant pear which told the history ofDorchester. Here was a miniature triple decker which looked almost like the one across the street. There was a baseball glove, for the Boston Resolutes, in the National Colored Base Ball League, who in 1887 went toLouisvilleto compete and won, but didn’t have enough money for the train ticket home. And there on another was a coil of rope cast in bronze with a small boat, the rope used by the earliest colonists fromEngland, by recent immigrants fromVietnam, and by others fromAfrica, who didn’t have any choice about coming, she said.

The man listened intently. Johnny and Laura introduced themselves and shook hands.

When I visited the sculptor Laura Baring-Gould in herSomervillestudio on another day, she told me about her involvement with theDorchesterproject. In 2002 she was invited to enter a contest to create a piece of public art inEdward Everett Squareat Five Corners. The local neighborhood and city government together were trying to restore some integrity to this intersection where, in the 1950s, Frederick Law Olmsted’s plan was obliterated in favor of more traffic lanes. By this time Dorchester was long annexed toBoston(1870) and the rich farmland gobbled up. The population had become heavily Irish, with smatterings of other ethnic groups. Newcomers from the Deep South as well asCape Verde, the Caribbean, andLatin Americawere soon to make it more of a melting pot, its Yankee and rural character mostly a memory.

Laura researched the neighborhood’s history, and some of her findings, beyond the scope of this article, went into the smaller sculptures around the giant pear in an effort to connect with the neighborhood. On this very spot in 1630 was the first English settlement of men, women and children, a few months ahead ofBoston. The Blake House (c.1661) stands a stone’s throw away, by the park where Edward Everett’s statue, his arms raised in gesticulation, was moved to make room for the pear.Everettlived in a mansion that stood on the corner, hence the square’s name, as a senator, governor, president of Harvard, renowned orator and public servant. He had the dubious distinction of speaking right before Abraham Lincoln atGettysburg, his two-hour speech followed byLincoln’s two-minute address.

A couple of blocks away, at195 Boston Street, stands the Clapp House, now home of the Dorchester Historical Society. This Federal-style house was built in 1806 by William Clapp, a successful tanner. Many vegetables and fruits were grown on the 300-acre estate in which his three sons took part, especially in breeding new varieties of pears. His son Thaddeus Clapp (1811-1861) kept detailed records of their experiments over many years. One particular pear cross, between theBartlett—thick skinned, early ripening—and Flemish Beauty—hardy and prolific, with juicy, sweet flesh—was his favorite, as it combined the virtues of each. Despite the Massachusetts Horticultural Society’s offer of $1,000 for the control of the hybrid, a sizable sum at that time, he wisely retained them. Though still grown, newer varieties have superseded it.

Diverse fruit hybrids developed by local horticulturalists in the 19th century bear their names or those of their towns: theDorchesterblackberry, President Wilder strawberry, Roxbury russet apple, Downer cherry, and Diana grape. Today you can find Clapp pear trees at195 Boston Streetas well as in private yards in the neighborhood and inBoston.

In 2009 a board member of the Dorchester Historical Society, based in the house where Thaddeus Clapp lived, suggested that they make a wine from Clapp pears. Pear wine is called perry, and inEnglandand other countries it has a long tradition. With the help of the Boston Winery, they gathered pears, topped off with some apples to have enough. They mashed the fruit and during the year went through the whole wine-making process, transferring if from tank to tank and eventually into barrels. They made 460 bottles of Dorchester Clapp Pear Wine, Vintage 2010, which they gave away to donors and to the people who helped them make it. None was sold.

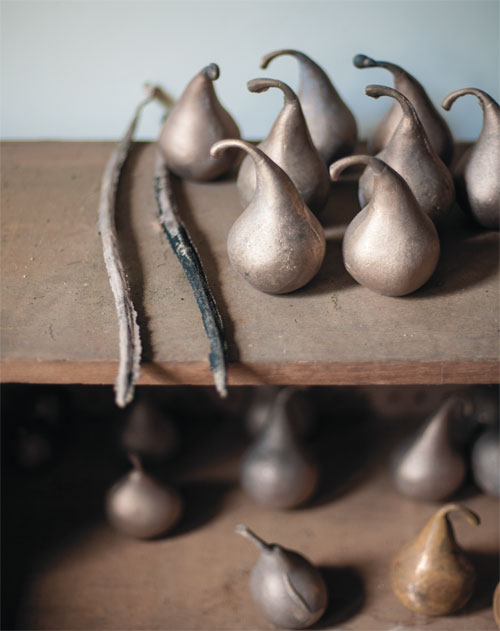

Laura Baring-Gould’s interest in pears had already begun before she discovered Clapp’s Favorite. In her studio she showed me a few of her small bronze pears. They look just like real pears in the act of decomposition, but weigh in at a heavy three to five pounds. “The Boscs are the good rotters,” she said. “I love how they sag and pucker and wrinkle.” Looking closely, the UPC symbol is visible in the shriveled bronze flesh. Each has its own anthropomorphic character beside the variety—squatting or leaning, humorous or voluptuous, stem upright or at a jaunty angle. “Some are just waiting for the bus,” she observed. The colorations vary slightly depending on the mineral content mixed into the copper with tin alloy.

Her kitchen window sills were lined with fresh pears, sitting there in the process of rotting for her next batch to cast. “They are fascinating to watch every day,” she said. “Autumn is the emotional harvest,” after the crops have been gathered in.

She began making these life-size pear sculptures in 1999. Bizarre as they may sound, they are beautiful to look at. After they have reached the desired state of decay, she covers them with a ¾-thick ceramic coating at a local foundry where they are fired to 2700˚ F. “The ceramic gets hard,” she explained, “and the pear burns and disappears as it’s reduced to carbon.” Finally she pours molten bronze into the cavity, and as it cools the ceramic cracks off. Now she uses a lost-wax process so that she can make multiple copies. She has made perhaps 1,000 bronze pears now, the sale of which support her other large-scale sculpture installations.

Holding a pear in the palm of her hand, she says, “this will be on the planet long after we’re gone, like the dogs ofPompeii.”

When I asked her about the challenge of casting the immense Dorchester Clapp Pear, weighing close to 1,500 pounds, she showed me a book of photographs. There she is pictured at a foundry inThailandwhich specializes in casting large-scale monuments and religious sculptures. Her visits took place over 2006 and 2007, after planning began in 2004, in time for the installation inDorchesterin 2007. The smaller sculptures were done in 2008 and 2009.

We knew the project “required the good will of everyone in the community,” she said. Making the local people aware of what they were doing was essential, and she dressed up as a pear in several Dorchester Day Parades. The challenge of engaging the locals remained. When they were installing the sculpture, the “squeegee guys” at the intersection were fascinated with the pear and became its docents, she said, telling passersby about the pear and how the square used to be.

To engage locals who cared about all the other parts of local history, Laura and the Edward Everett Project Committee devised the brick project, in recognition ofDorchesteras headquarters for the brick-laying union. The Bricklayers and Allied Craftsmen Union Local 3 Apprentice Training Center donated their time and skill to laying the 25,000 bricks in the park around the pear. The project is ongoing. People in the neighborhood and beyond have bought them at $100 apiece and chosen their personal inscriptions to be cut into the brick. Besides those commemorating family members and romantic partners while supporting the project, she pointed out some unusual ones, such as The Dorchester Crew Villains, a local gang. Another read, simply, “Remember Smitty.”

On hearing this, Johnny decided that he wanted to buy a brick. Although Laura told him they could help him do it, he insisted on buying it himself and giving it in memory of his mother.

We looked up at the great pear with its little nubbin of a neck, curved stem and subtly textured surface. Clapp’s Favorite, Laura reminded me, has a tough skin with a soft and tender interior—like the people ofDorchester.

In addition to Laura Baring-Gould, special thanks to:

Earl Taylor, President of the Dorchester Historical Society; John McColgan, Chairman, Edward Everett Square Project Committee; The Bricklayers and Allied Craftsmen Union Local 3 Apprentice Training Center; The Au Pears; The Residents of Dorchester and especially those of Edward Everett Square. The Dorchester Pear was funded by grants from the Edward Ingersoll Brown Fund (Dorchester Clapp Pear) and The Henderson Fund (smaller works). The City ofBoston.

Elizabeth Gawthrop Riely’s articles have appeared in many newspapers and magazines. Her cookbook, A Feast of Fruits, was published by Macmillan in 1983. Her dictionary, The Chef’s Companion (John Wiley & Sons, 3rd edition), remains in print after 25 years. She was editor of The Culinary Times, published by the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, from 2000 to 2009. Her article on “John James Audubon’s Tastes of America” was in the Summer 2011 issue of Gastronomica. Beth can be reached at elizabethriely@gmail.com.