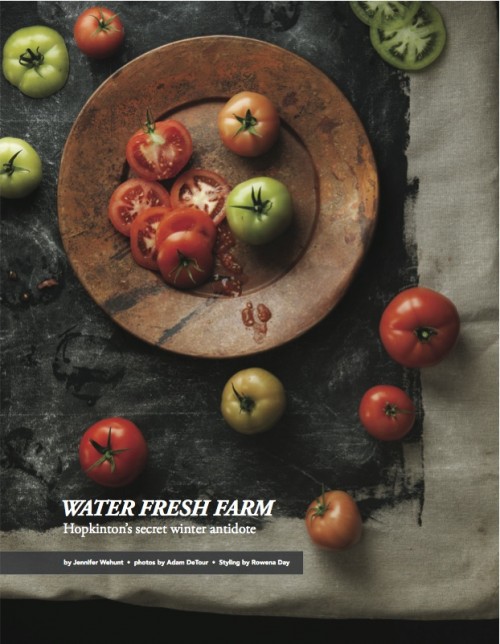

Water Fresh Farm

Water Fresh Farm: Hopkinton's Secret Winter Antidote By Jennifer Wehunt/Photos by Adam DeTour

The most desirable seat in Hopkinton isn’t the mayor’s chair. It isn’t the high school homecoming throne or a prime position along the starting line of the Boston Marathon, which begins every April in this bucolic town of 15,000 people some 30 miles west of Boston. In winter, at least, the best seat in Hopkinton is a rough-hewn blond wooden bench, also known as the observation deck, just inside the hydroponic greenhouse at Water Fresh Farm.

Here, while the snow piles up outside and the wind howls and moans, the light is always pure, the landscape is always in full vertiginous bloom, and the daytime temperature always hovers around 70 degrees.

But you might have to fight for it. The bench is only 30 feet long, and when the locals move in with their newspapers and their cups of fair-trade coffee and whole-grain banana muffins purchased in the market out front, space gets tight. And if competition is fierce for the bench, you can imagine what it’s like come January for the tomatoes. That’s right: The greenhouse grows beefsteak tomatoes year-round, even in January.

For those not familiar with the term, hydroponics refers to a method of growing plants in which soil is replaced by an alternative medium—burlap, for example—with nutrient-rich water piped straight to the roots of the plants. The practice has been around for thousands of years, in B.C. Babylon, in Aztec-era Mexico, and, to the surprise of many locals, in west suburban Hopkinton since 1997, when Jeff Barton and a business partner opened Water Fresh Farm.

Entrepreneurs at heart, the two lifelong friends and UConn grads hit upon the idea of hydroponics and followed their hunch to the University of Arizona. There they completed a training course with the father of modern hydroponics, Dr. Merle Jensen, who still checks in with Water Fresh each week as a consultant—or, in his words, a coach. “You have a coach in basketball, so why not hydroponics?” he quips.

Fast forward a decade-plus: While the owners saw many changes over the years—including the expansion of their original 5,400-foot greenhouse into a six-bay, ½-acre affair—hydroponics remains foreign to the average consumer. Because Water Fresh sells the majority of its produce to chains such as Whole Foods and Roche Bros., shoppers didn’t have cause to venture into the greenhouse. Which got the guys thinking: Perhaps hydroponics deserved a platform—a public debut, as it were. So, in early 2012, after a year of construction, Water Fresh Farm birthed Water Fresh Market, which is like a regular old grocery store in the way that hydroponics is like regular old farming.

Built to spec from eco-friendly New England lumber, the market looks like a swanky barn and feels like a neighborhood coffee shop. There is fresh produce, grown both in the attached greenhouse and by other farmers; a carefully-chosen selection of artisanal packaged goods; and a deli counter, bakery, and prepared-foods case full of heat-and-eat meals crafted by the market’s chefs. But more than the gentle tinkling of water in the market’s copper-hewn fountain or the aroma of seafood stew wafting from the state-of-the-art kitchen, shoppers notice the feeling. “People love coming in here because it feels good,” Barton says.

January 2013 marks the market’s first year in operation and the first full winter when customers can stop by to pick up some fresh-plucked basil or a roast beef dinner and sit for a spell on that sauna-like deck. But to fully understand the market and why it works, you first have to understand its roots. Its gargantuan, 35-foot-long roots.

“Here we’ve got lettuce, basil, baby spinach. And over there are the herbs: cilantro, chives, mint—we’re just starting with the mint. And here are the microgreens. These are brand new for us. We’re still figuring out what types we can grow. We’ve got a spicy mix—awesome wasabi flavor, great on a turkey sandwich—and mustard greens that are like, pow! So intense. This one is ready to harvest. We just shave it off the burlap, two weeks after dropping the seeds. It’s that quick.”

Wiry, athletic, and always on the move, Jeff Barton tours his greenhouse like a kid in a candy store, pointing out the towering buckets of emerald-green cilantro, the heads of bibb lettuce bobbing like apples in their shallow pools, the cucumber vines that flutter ever so gently, suspended from the ceiling by strings like leafy marionettes.

In 2010, Barton, who comes from a high-tech background, left his day job in software research to oversee the farm full time. Even now, the newness hasn’t worn off, maybe in part because Barton, 50, is thrilled to have his hands on a living, growing, tangible product and maybe in part because the farm is always evolving—within limits.

“Backyard Farms, up in Maine?” Barton offers. “It’s owned by Fidelity. A really lovely guy started it, but within a year, he was gone. That wasn’t the point for us. We didn’t want to expand to be as big as we could be. In the corporate world, you have to execute stuff that other people decide, whether or not you think it’s the right thing to do. Here, we wanted to make decisions that we could believe in.”

One of those decisions has been to stick with high-quality crops. Although Barton says many greenhouses have switched over to an easier to grow tomato, Water Fresh has stayed the course with beefsteak, which he calls a superior variety. And while the farm has increased its output to include Italian sweet basil, Boston bibb lettuce, baby spinach, and, as of 2012, microgreens and herbs, all of which are sold almost exclusively in the onsite market, the farm’s mainstays—and the linchpin of its wholesale business—remain its two original two crops: Persian cucumbers and tomatoes. Make that Persian cucumbers and giant tomatoes. A single beefsteak tomato plant can grow upwards of 30 feet in length and, unlike the most attentively nursed backyard specimen, can thrive for 10 months or more.

That longevity is due to an obsessively monitored system. Here’s how hydroponics works: Every plant starts out as a seed nestled in a growing medium, sometimes plain old burlap, sometimes a blend of spun rock fibers, called rockwool, and coconut husk. Each seed pack has roughly the same dimensions as the average seed-starting cell used by any gardener, about the size of a Dixie cup. But where a soil-raised seedling would get transferred to a bigger pot or into the ground as it grew, a hydroponic root bundle remains neat and compact for its entire lifecycle, while the top of the plant—the fruit-bearing foliage—flourishes.

The palm-sized packet, the plant’s heart and soul, is able to stay so small because it doesn’t have to go looking for food. It gets plenty of what it needs—nutrient-enriched water—delivered straight to its roots through an IV-like system, although the exact diet changes from plant to plant. Not only do tomatoes get a different ratio of nutrients to water than cucumbers, but a mature tomato plant gets a different ratio than a wee sprout. “Just as you wouldn’t feed an infant the same thing as you’d feed a toddler as you’d feed a teenager or an adult, plants are like that, too,” Barton says. “We follow the lifecycle of the plant and give it what it needs at that stage in its life.”

The fine print: Hydroponics isn’t organic, exactly. Because there is no soil, there’s no fertilizer to earn a certified-organic seal. But, as is the case at Water Fresh Farm, the process can be pesticide free, with several distinct benefits. Because growing takes place indoors, in a controlled environment, the plants produce year-round (in other words, fresh-picked tomatoes in January); when properly managed, the method uses less water than conventional farming; and, in place of environmentally unfriendly chemical sprays, certain insects cans be introduced to fight common plant ailments, such as powdery mildew.

These efficiencies can also make hydroponics more productive than conventional farming—up to 10 times more productive in New England, some experts suggest. You feed the plants the nutrients they need, when they need them, urging them to yield bounteous fruit but not stressing them so much that they revert to producing more inedible leaves and fewer delicious cucumbers.

And yet, just because the plants are protected from the outdoors doesn’t mean they’re low maintenance or invulnerable. The slightest shift can throw off this fragile indoor ecosystem, which is why computerized sensors located throughout the greenhouse measure minute fluctuations in temperature, in moisture, and in light, alerting the plants’ tenders when adjustments are necessary. Just as humans perspire more on days when it’s hot and humid, plants transpire more, too, Barton says, and need more to drink. And on days when heavy snow accumulates on the greenhouse roof or, God forbid, the power goes out, response time can be critical.

“We had a power outage three days ago, and the temperature raised probably nine degrees in 15 seconds,” says Barney Borovoski, Water Fresh Farm’s greenhouse manager. “Without electricity, in the summer, the plants can die in three hours. And last January we got blasted with two feet of snow, so we had to crank the heat. If something happens and you’re not prepared, it can ruin the business. But I’ve been here a long time now, and I know the kinds of problems that can develop.”

In his 11 years at Water Fresh, six as greenhouse manager, Borovoski hasn’t only responded to crises; he has helped the farm innovate. Like Barton, Borovoski, a 35-year-old Brazilian native with a jovial grin, started out in the tech industry. And while his IT background has been invaluable in running Water Fresh’s computer network of sensors—its HAL, as it were—he’s not so focused on the forest that he can’t see the trees.

“I’m a self-taught guy,” Borovoski says. “Before I got to be manager, I was very involved with taking care of the plants. And being involved with plants, that’s natural for a human being.” Borovoski remains elbow-deep in the flora, and, from his bug’s-eye perch, he notices things—like in 2009, when staff realized that if the tomato vines didn’t lie directly on the gravel floor, the air might circulate around them better, making the plants less susceptible to disease. Hence the low metal piping that now runs the length of the greenhouse, lifting the tomato vines off the ground like risers supporting children in a choir.

Borovoski can get a little paternal toward his plants. “You’ll be walking through the crop and see a broken leaf tip, and you get upset,” he says. “And then you see another broken tip. Two in a row! Sometimes I go to bed, dreaming about how we can solve things.” Borovoski pauses, looking genuinely ruffled, before continuing. “My son is two years old, and I’m trying to raise him the best I can. It’s a different feeling, of course, but I’m just as preoccupied with what’s happening here.”

The sense of personal investment is even more present inside the market. If the greenhouse is Barney’s realm, the shop and all of the food and people in it fall under Barton’s domain, and he takes his role as master, commander, and all-around-nice-guy-in-chief seriously. It’s what allows him to say things like, “We’re in the business of nourishing,” or “We’re a sanctuary for fresh food,” and mean it.

That earnestness has won the market a small but intensely loyal following. Comments from shoppers on the farm’s Facebook page read like Justin Bieber–caliber fan mail—“What a great addition to our community!” and “We saw your opening signs for the last month and could not wait to pay a visit to your wonderful farm store!” and “So happy! Everyone must go!”—or, occasionally, like something even more personal: “Thank you Water Fresh Farm for tracking me down through the Hopkinton Public Library card on my key ring to let me know you had my keys!”

Barton envisions the market as the kind of place where locals drop in a couple of times a week—to pick up spinach, maybe, or for the nightly “Hot for the Family” special. And, for the most part, his vision has come to pass. Many people in the community speak at length about Barton and how they see him as central to the store’s welcoming vibe. They talked about him, in fact, like family.

Which begs the question: You might be on a first name basis with a farmer at your local farmers market, but when was the last time you thought of your grocer as a friend? A trusted confidant? In truth, it may be something of a two-way street. Barton’s wife passed away two years ago, and, in a sense, the business, its employees, and even its customers have become his extended family—in a literal sense, too. Michael Welch, the market’s executive chef, is Barton’s brother-in-law. “I love it here,” Welch says, without a hint of my-relative-is-the-boss strain. Although Welch has spent years working in kitchens from upscale seafood restaurants to Connecticut’s Lyman Orchards, he gets downright giddy talking about what he thinks sets Water Fresh apart.

“It’s just awesome to be able to go into the greenhouse and pick my own basil, to go out there and feel it and touch it and smell it,” he says. “It’s such a different experience than going into a walk-in refrigerator and ripping open a cardboard box. There’s a lot more pride when you’re cooking if you’re thinking, ‘We grew that here.’”

Barton is banking on shoppers feeling the same thing, that same local pride, with the same level of engagement. If anything, the challenge for Water Fresh—essentially, a family-run business in a small, if well-to-do, town—is finding ways to expand its somewhat limited customer base. But Barton is working on it. In a way,a the greenhouse is the perfect metaphor for the relationship between the market and the farm, and between the business and its community: There’s transparency. It’s a space full of light, where things grow.

“I never would have said I would end up a farmer,” Barton admits during a rare moment sitting still. “I thought I would be a professional baseball player. But my mother’s family, from the Midwest, were farmers—dirt farmers, basically. So, in some sense, it’s in my blood.”

Or, you could say, in his roots.

Barton hosts a talk on hydroponics every Saturday at 11am on Water Fresh Farm’s observation deck. Attendance is free.

Water Fresh Farm 151 Hayden Rowe Street, Hopkinton 508.435.3400 www.waterfreshfarm.com

A former senior editor at Chicago magazine who recently relocated to the Boston area, Jennifer Wehunt likes to write about food almost as much as she likes to eat it. She's currently in the market for kohlrabi recipes; email her at wehuntwolff@gmail.com.