Growing Resilience: How Moveable Greenhouses Are Helping Siena Farms Extend the Season and Improve Climate Readiness

Photos by Michael Piazza

When Chris Kurth and wife and partner Ana Sortun started Siena Farms in Sudbury in 2005, they had one small, unheated greenhouse for sprouting seedlings. The farmers’ biggest concerns then were making sure there was a market for locally grown produce and scaling up production as needed.

In those early years, the farm’s growing season would end around Thanksgiving; most of the staff would go home and things would shut down for the winter. The farm would wake up again for a new season with new growth in the greenhouse around March.

Nearly two decades later, every part of that picture has changed.

Now, there’s no question about a thriving market for high-quality, locally grown food in Eastern Massachusetts. Siena Farms’ 2,000 community-supported agriculture (CSA) harvest subscription members, two retail outposts in Boston’s South End and Boston Public Market and 100-plus varieties of produce are proof of that.

The long winter break is also a thing of the past.

Siena’s staff is now busy all year growing crops to support the CSA memberships, stores and wholesale business, thanks in part to a serious upgrade from that lone greenhouse of 18 years ago.

On an unseasonably hot and uncharacteristically dry— for this growing year, at least—October afternoon, Kurth offers a tour of the farm’s nine new greenhouses in Sudbury. A tenth greenhouse is located in Sterling.

These new structures will soon be teeming with hearty winter kale and baby salad greens that will offer a welcome taste of local fresh food in the depth of New England winter.

Construction of the greenhouses was funded with grants from the Massachusetts Food Security Infrastructure Grant Program (FSIGP). The program was created during the early days of the COVID pandemic to ensure individuals and families have access to food, with a special focus on food that’s locally produced, and that food producers are connected to a strong, resilient local food system with minimal supply chain disruptions.

Now in its third year, the program awards grants to farmers, fishermen and other local food producers for capital infrastructure investments, such as Siena’s new greenhouses that support year-round food production.

“Our CSA distribution, retail and wholesale sales go year round, but we never had many greens in the winter,” Kurth says. “We grow lots of root crops and other storage crops. The most important way to better service our customers in the winter and the spring is to grow more greens.”

The Russian and Winterbor kale that will be part of the farm’s winter offering are getting started directly in the ground in front of several of those new greenhouses.

These greens, which went in the ground in September, will continue growing in the fields until they are ready to harvest in January.

The plants won’t be moved. The greenhouses will.

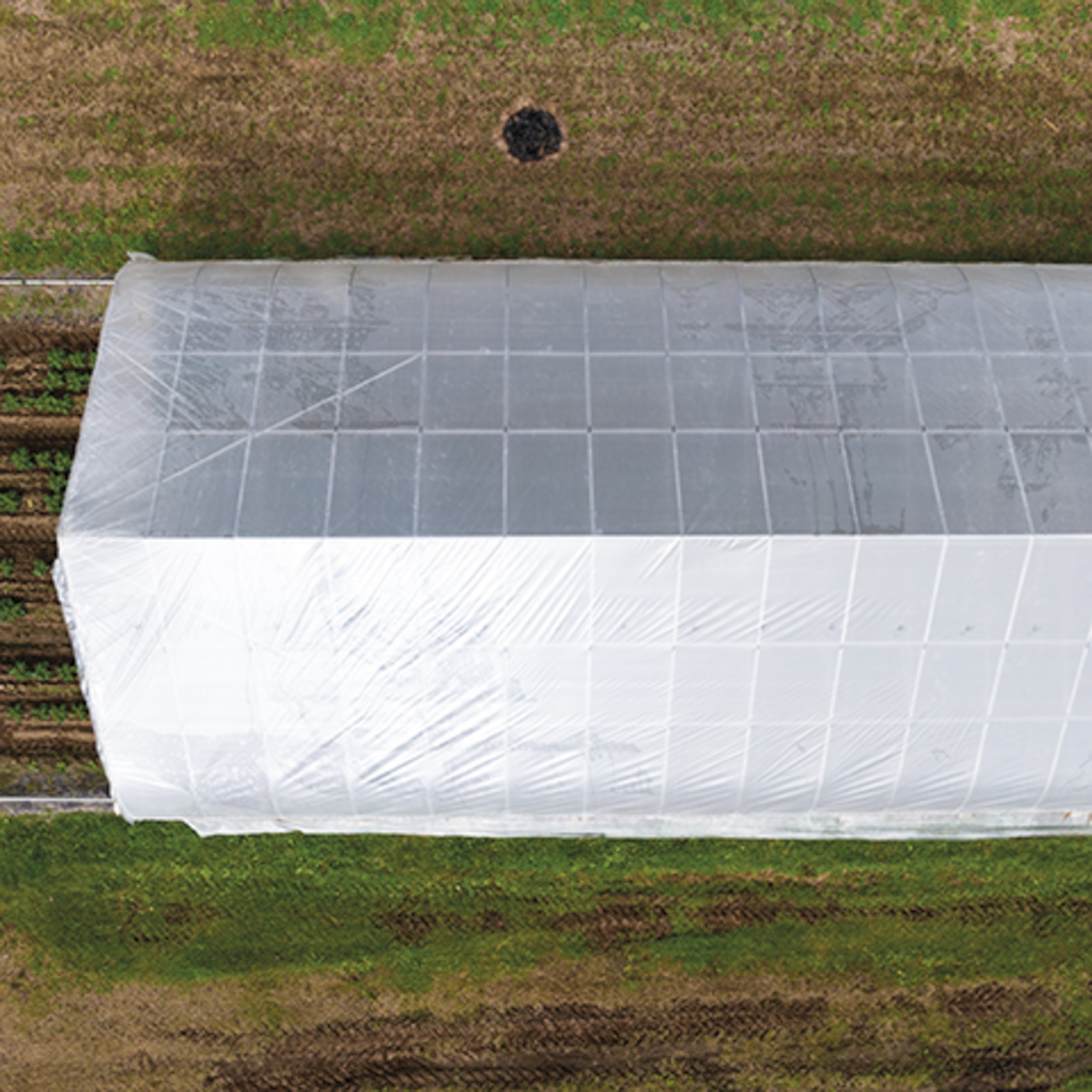

Siena Farms’ five portable Rolling Thunder greenhouses (also referred to as high tunnels) move on rails back and forth to different areas of the fields. In October, the 30- by 72-foot greenhouses still house fresh ginger, a rhizome the farm gets from Hawaii that wouldn’t typically thrive in New England growing conditions. The moveable greenhouse gives it the shelter it needs.

When the final ginger harvest is completed and the weather gets colder, the Siena team will flip up hinged panels on the fronts and backs of the greenhouses, untether them from the stakes that hold them in place, then six to eight people will roll each building along rails to its next location over the winter kale crop.

“You just push it along. And once you get going, it kind of moves easily on its own,” says Peter Staub, Siena Farms’ greenhouse manager.

Once in place, the buildings are re-staked into the ground. They then use passive solar energy—but no external heat sources—to keep the kale crops growing until they are ready for harvest around the new year. When the kale harvest is complete, the growing cycle continues as farmers prepare the soil and get started on early spring lettuces, baby bok choy, spinach and other greens.

Staub explains that the design of the greenhouses includes a double layer of plastic that traps air in between for extra insulation. It also helps magnify the sun to retain as much heat as possible. Staub says that even in the winter the greenhouses can warm enough during daytime that they need to open vents to release excess heat. When nighttime temperatures dip very low, the farmers use hay bales and cover fabric to insulate crops.

For these greenhouses the Siena team chose hearty kale varieties that are less sensitive to temperature variations than the salad greens that will be grown in the farm’s four conventional stationary greenhouses, which are heated with propane to maintain a more constant temperature.

“There’s some benefit to having these plots uncovered right now because even though it’s not super cold, getting exposure to more environmental conditions at the early stages of their life like this, when they are strong enough to withstand it, makes them even stronger. So come winter, when it’s really, really harsh conditions, they are primed to survive,” Staub says.

According to Kurth, the new moveable greenhouses are part of a larger trend toward more indoor growing that represents a “new frontier” for agriculture.

“This is very cutting edge, not just in New England but in other parts of the world—especially given what climate change is already bringing to agriculture in every corner of the planet and is predicted to increasingly make outdoor food production even more challenging. I don’t envision a world where the majority of food is grown indoors, but that’s definitely one of the several key adjustments I think farmers are making,” Kurth says.

He notes that the past three growing seasons in Massachusetts have all been impacted by extreme weather conditions: excessive rain that damaged crops in 2021 followed by drought conditions in 2022 and record rains and flooding in 2023.

“So that’s three out of three years we’ve had extreme weather events all summer long. We kind of actually expect that that’s now the norm,” Kurth says.

Controlled growing is one of several ways he says Siena Farms is adapting to extreme weather. In addition to the greenhouses, Siena uses separate controlled growing environments for mushrooms. Kurth says he is also looking to lower the risks of flooding and drought by improving drainage and irrigation in outdoor fields, and planting a wide array of crops, with the understanding that some will be lost to weather conditions.

In 2023, Butternut squash yields were up 50%, although other winter squashes didn’t fare as well. Tomatoes were the bumper crop in the dry weather of 2022, with yields 10 times higher than in 2023. Kurth hopes that by diversifying and improving field irrigation and drainage, they can limit losses to no more than 20% of what is planted each year.

Encouraging projects that address climate resiliency has become a key focus of the Massachusetts Food Security Infrastructure Grant Program, which also has combating food insecurity as a major goal. It was initially created to address food security during the pandemic. Siena received grants totaling $380,000 in the first two years of the grant program. The farm used the grants to build the new greenhouses, as well as install a new irrigation system that serves several fields.

In July, Governor Maura Healey announced the most recent FSIGP awards totaling more $26.3 million and supporting 165 projects.

“In speaking to farmers over the past week, it’s clear that they need support now more than ever after being hit hard by extreme weather events from flooding to drought to late frost. Our farmers are the backbone of Massachusetts’ food infrastructure, and it’s critical that we continue to make short- and long-term investments through grants like these to help strengthen resiliency and enhance mitigation efforts,” Healey said in announcing the 2023 grants.

Although Siena Farms did not receive a grant this year, Kurth remains thankful for the support the state has provided him and other local farmers, especially during the COVID pandemic.

“They have really rolled up their sleeves to recognize the increasing challenges that farmers are facing with climate change. They’re also recognizing the increasing importance of having a strong regional food system, not just in times of crisis. That’s the key foundation of a healthy, resilient society. It’s having a robust agricultural system underpinning human health and human communities,” Kurth says.

Greenhouse manager Staub concurs, noting that the people who practice local agriculture have worked for a long time to build “a resilient and flourishing” local food system.

“We have a really unique opportunity in this area to have large-scale access to farmland in close proximity to cities,” Staub says. “If you take the proposition of local agriculture reducing the climate impact and fossil fuel usage for transporting food around, we’re doing it to a big degree because of the density of this region. That’s something that’s really exciting working here. I’m at a farm where people care about these issues and it feels like we actually have an impact.”

This story appeared in the Winter 2024 issue.