A Global Taste of Passover: Celebrate the Festival of Freedom with Tantalizing Passover Food From Around the World

Come Passover, as families and friends gather around the festive seder table for the ritual-filled ceremony and meal, they will retell the 4,000-year-old biblical story of Exodus that celebrates freedom from slavery.

In 2025 the eight-day holiday—also known as the Festival of Freedom—begins on the evening of Saturday, April 12.

Matzah takes center stage at the seder and throughout the holiday; the flat, unleavened cracker is a reminder that the ancient Israelites, who were enslaved in Egypt, had to flee their homes in haste and didn’t have time to bake bread.

For hosts who want to broaden their holiday menu with global Jewish cuisine, there’s a wide array of tantalizing recipes and cookbooks embracing the diversity of Jewish life and traditions from across the globe.

Stir up a crispy Jewish-Mexican Passover version of chilaquiles, the popular Mexican dish, made with fried strips of matzah, eggs and tomatillo salsa; frost a luscious seven-layer matzah cake from the family of a Polish Holocaust survivor; or fry up a batch of Roman Pizzarelle con Miele, a sweet matzah fritter drizzled with honey.

Among the tastiest ceremonial seder foods is haroset—a flavorful blend of apples, nuts and sweet Passover wine that’s eaten with grated horseradish on matzah or greens—a symbol of the bitterness of slavery and the sweet taste of freedom.

Traditional Ashkenazi haroset, from Eastern and Central Europe, uses coarsely chopped walnuts with the apples and wine.

Sephardic Jews, who fled the Spanish Inquisition at the end of the 15th century and settled across the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, make their haroset with dried dates, raisins and apricots, along with almonds, pistachios and chestnuts, inspired by what was available in the markets of their new locales.

When Rachel Sundet was growing up, her family’s seder table boasted a version of Sephardic haroset from her South-African father’s family. All these years later, Sundet, the award-winning pastry chef and one of the co-owners of the popular Jewish delicatessen, Mamalehs, serves her updated version at her family’s seder.

“It can be used as a base for whatever dried fruit you have in the pantry,” she tells Edible Boston. This haroset ends up dark and sticky, and is very delicious.” (See the recipe below.)

Edible Boston checked in with chefs and writers from all over Greater Boston and New England, whose family roots span the Jewish diaspora, for a taste of what’s on their Passover menus—and for the stories that bring the food to life.

Matzah Chilaquiles (recipe below) is among the Passover recipes featured in Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook, by Ilan Stavans and Margaret Boyle, both Jewish Mexican-Americans. Stavans, who was born in Mexico City, is a professor at Amherst College and a leading scholar on Latin America.

Boyle, who grew up in Los Angeles, is an associate professor at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, where she directs its Latin American, Caribbean and Latinx studies program.

The Passover version of chilaquiles is a must-have in Boyle’s family, first sparked by her father’s love of the popular Mexican dish of eggs, tomatillo salsa and corn tortillas.

Boyle remembers visiting her maternal great-grandmother in Mexico City during Passover when she made her kosher-for-Passover version of chilaquiles by swapping strips of matzah for the traditional corn tortillas.

Stavans says matzah chilaquiles are central to Mexican and Jewish-Mexican cuisine and bound up with their cultural identity, and they hold pride-of-place on the Stavans’ seder table.

“For me, they are our way of grounding the eight days of the holiday. I get tired of matzah,” he says with a chuckle.

On the sweet side, Jews in Rome are known for creating Pizzarelle con Miele: sweet, fried matzah fritters, dipped in honey (recipe below).

Simona Di Nepi, who grew up in a Jewish family in Rome, has fond childhood memories enjoying the pizzarelle that her paternal grandmother, whose Roman Jewish family survived the Holocaust, served for the holiday.

Di Nepi, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman curator of Judaica at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, says that the fritters share a name with pizzarelle, a Roman hamburger, because the Passover treat, made with matzah that’s been soaked in egg and crumbled, resembles the ground meat patty.

“I remember so vividly being in my grandmother’s apartment, with its very small kitchen, and her telling me not to go into the kitchen when the pizzarelle were on the paper towels soaking up the oil,” she says.

As a kid, Di Nepi couldn’t resist and she’d sneak a few of the tempting treats.

A dessert that graces the seder table at Janet Stein Calm’s home is Seven-Layer Frosted Matzah Cake, a no-bake, refrigerator cake that her Hungarian mother, Bluma, made every Passover (recipe below).

Stein Calm’s Hungarian father was a Holocaust survivor. The matzah cake was her mother’s signature recipe, an adaptation of a Hungarian dobros torte, a seven-layer cake made with sponge cake.

Devoting the time to prepare the cake for her large, multi-generational family seder is a labor-of-love and remembrance for Stein Calm, president of the Association of American Jewish Holocaust Survivors of Greater Boston.

“It was light and delicious,” Stein Calm recalls all these years later. Serving the cake ensures that the fond memories of her parents’ families are ever-present, she says.

The cake, made with just one egg, is welcome this year because of the limited supply of eggs and high prices.

The shortage is a cause of concern for Stein Calm, who like many others preparing for Passover, easily goes through some 10 dozen eggs for the holiday, when they’re eaten as part of the seder ritual as a symbol of renewal. They’re also used for leavening in matzah balls and many other recipes. Jewish Telegraphic Agency wrote about this issue earlier this month.

Another Passover perennial for Stein Calm’s family is klops, a dish she learned from her mother. It’s an oval-shaped meatloaf with a hard-boiled egg tucked inside. Like her mother, she makes small, individual-sized ovals, perfect for a packable lunch during the holiday.

This Passover, at a time when many people are concerned by widespread hunger around the world, celebrating Passover with family and friends is a way to express gratitude and offers a promise of renewal and hope for better times.

RECIPES

Rachel Sundet’s Haroset With Dried Fruit and Ginger

When Rachel Sundet was growing up, her family’s seder table boasted a version of Sephardic haroset from her South-African father’s family. All these years later, Sundet, one of the co-owners of Mamalehs, where she’s the award-winning pastry chef, serves her updated version at her family’s seder. It’s a versatile recipe that can be used as a base for whatever dried fruit you have in the pantry, she said. This haroset ends up dark and sticky, and is very delicious, she says.

200 grams (or 1½ cups) dried apricots

120 grams (or ½ cup) dried figs

55 grams (or ½ cup) golden raisins

55 grams (or ½ cup) currants

30 grams (or ¼ cup) ginger, finely diced

30 grams (or ¼ cup) apple cider vinegar

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

2 apples, diced

180 grams (or ¾ cup) Concord grape wine

100 grams (or ¾ cup) walnuts, toasted

salt, to taste

In a large bowl, stir all the ingredients together except for the walnuts and salt and allow to soak, preferably overnight.

Stir in the walnuts, transfer to a saucepan and gently cook over low-medium heat until apples are tender.

Pulse gently in a food processor; do not purée. There should be some texture. Season with salt to taste.

Matzah Chilaquiles

From Sabor Judío: The Jewish Mexican Cookbook, a new, award-winning book by Ilan Stavans and Margaret Boyle.

Chilaquiles, typically freshly sliced and fried tortilla strips bathed with freshly prepared red or green salsa and eggs, a mainstay of Mexican daily life, are often served for breakfast. But the dish is also enjoyed throughout the day. In this Passover version, humble matzah holds the flavors of chilaquiles in unexpectedly delightful ways. The co-authors say that the spice of this recipe is a relief for those exhausted by the taste of matzah by day three or four of Passover.

Serves 2 (recipe can be doubled)

Vegetable oil, for frying

4 squares matzah

½ medium red onion, thinly sliced

¼ teaspoon kosher salt, plus more for sprinkling

4 large eggs, lightly beaten

1 cup store-bought tomatillo salsa

Queso fresco, Mexican crema and chopped fresh cilantro, for serving

Heat ¼ inch of oil in a large frying pan set over medium heat until shimmering, and line a large plate with paper towels.

Working with one piece of matzah at a time, fry the matzah, turning once, until golden and crisp, about 2 minutes per piece. Transfer to the paper towels to drain, then break up into bite-size pieces.

Pour out and discard all but 2 tablespoons of the oil from the frying pan. Add the onion and salt and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened and lightly browned, 6–8 minutes.

Add the eggs and cook, stirring often, until scrambled, about 2 minutes. Add the fried matzah pieces and salsa, stir, and allow to heat through.

Divide between plates and sprinkle with a little more salt. Top as desired with queso fresco, crema and fresh cilantro.

Pizzarelle con Mieli (Honey-Soaked Matzah Fritters)

Adapted from Silvia Nacamulli

For Passover, Roman Jews are known for their sweet delicacy—a matzah fritter drizzled with honey. This recipe is adapted from one by Silvia Nacamulli, a highly regarded cookbook writer and authority on Italian-Jewish foods and was suggested to Edible Boston by Simona Di Nepi, the Italian-born and raised curator of Judaica at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, who’s a friend of Nacamulli. Every Passover, Di Nepi, who grew up in Rome, looked forward to the treats that her paternal grandmother fried up in her small kitchen. Some people add cocoa for a chocolate variation.

5 pieces of matzah

3 eggs, lightly beaten

½ cup sugar

½ cup high quality cocoa (optional)

¼ cup unsalted pine nuts, lightly toasted

¼ cup raisins, soaked in warm water for 5 minutes and drained

2 cups neutral oil such as sunflower, for frying

juice of 1 lemon

¼ cup honey, for dipping

Soak the matzah in a bowl of cold water for 15 minutes, until soggy. The matzah can be broken into large pieces, or soaked in a square baking dish. Drain and squeeze out excess water.

While the matzah is soaking, in a large bowl mix the eggs, sugar, cocoa (if using), pine nuts and raisins.

Add the drained matzah pieces to the bowl and stir until well combined. Divide the mixture into ping pong-sized balls and flatten into patties; refrigerate for at least 10-15 minutes before frying.

When ready to fry, heat the oil to about 325°F. Line a large plate or baking tray with paper towels. Working in batches, fry fritters on each side for approximately 2-3 minutes, flipping once, until both sides are golden brown. Place the fritters on the towel-lined baking sheet to absorb any excess oil.

Heat the honey, lemon juice and a few teaspoons of water over medium heat for about 4-5 minutes, until pourable. The honey should bubble but not burn.

Serve the hot fritters immediately with the warm honey drizzled over the top.

Seven-Layer Matzah Cake

Janet Stein Calm, president of the American Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors of Greater Boston, makes this luscious dessert every Passover; it’s a labor of love and remembrance of the cake made by her Hungarian mother, Bluma. Her Hungarian father was a Holocaust survivor. The recipe was intended as a way to use up leftover matzah at the end of the holiday, but Stein Calm’s mother thought it was perfect to serve for the seder. The no-bake refrigerator cake comes together as seven squares of matzah are dipped in white wine, frosted and stacked on a platter. The top and sides of the cake are frosted, before chilling the cake.

Serves 8–10

1½ cup superfine sugar

2 sticks butter or kosher-for-passover pareve margarine

1 egg or equivalent in pasteurized egg whites

1 tablespoon high quality cocoa

2 tablespoons instant coffee or warm coffee

7 squares of matzah

3–4 cups white wine, for dipping

Dark chocolate, shaved, for decorative topping

For the frosting:

In a large bowl, beat the sugar and egg until fluffy. In a cup, stir together the cocoa and the coffee to make a paste; fold into the frosting. Set aside.

To assemble:

Pour the wine into a square baking dish and dip matzah, one square at a time, into the liquid; remove quickly. Using an offset spatula, spread frosting on both sides of one piece of matzah and place on a cake serving platter. Repeat with the remaining matzah, stacking each frosted square on the platter.

When all the matzah squares have been frosted, spread the remaining frosting to cover sides and top of cake.

Decorate with shaved chocolate and cover the cake loosely with plastic wrap; chill for at least four hours before serving, until matzah softens.

Felipa Cardosa’s Chestnut Matzah

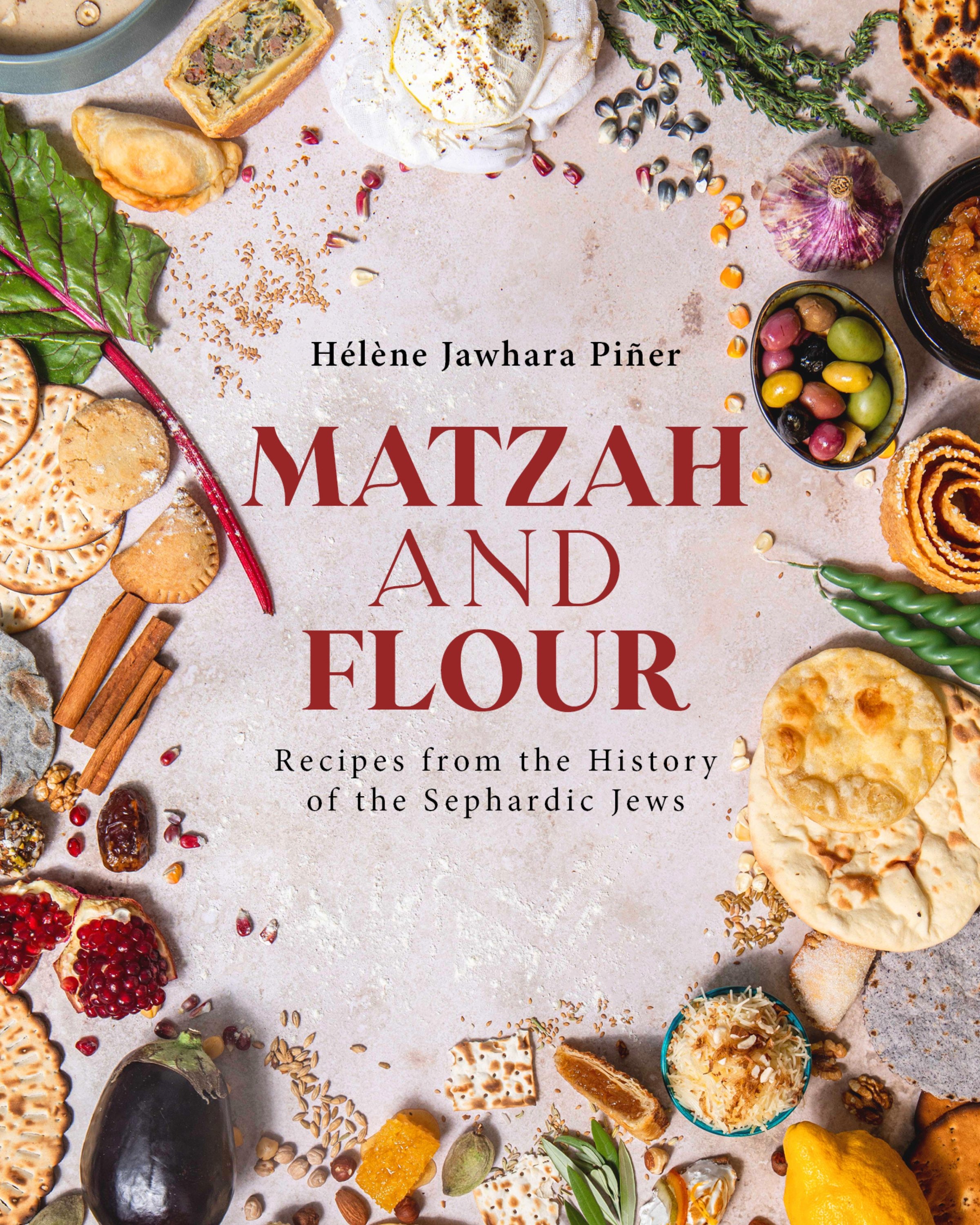

This intriguing recipe for small rounds of matzah made from chestnuts, is adapted from Matzah and Flour: Recipes from the History of the Sephardic Jews, a new cookbook by Hélène Jawhara Piñer, embellished with stunning photographs. Jawhara Piñer, a scholar of Sephardic food, discovered this recipe—and the others in this book—in her research of Inquisition-era trials of Jews in Spain, Portugal and even Mexico. You can find cooked, peeled chestnuts sold in jars or in foil packets in many supermarkets and online.

Makes 8 round pieces of matzah

1 cup or (20 pieces) chestnuts, either unpeeled, or store-bought, pre-cooked

1 cup chestnut flour

2 teaspoons salt

4 tablespoons water

To cook whole chestnuts in the shell, using a sharp knife, make a small X-shaped incision on the flat side of each chestnut using a sharp knife. This helps prevent them from bursting during boiling and makes them easier to peel later.

Rinse the chestnuts under cold water to remove any dirt or debris. Place the prepared chestnuts in a large pot and cover them with enough water to submerge them completely. Bring the water to a boil over high heat.

Once the water is boiling, reduce the heat to medium-low and let the chestnuts simmer for about 20–30 minutes.They are ready when the shells begin to peel back, and the nuts inside are tender. Once boiled, drain the chestnuts and let them cool for a few minutes until they are safe to handle. Peel the chestnuts and mash them while they are still warm. The shells should come off easily.

If you are using store-bought cooked chestnuts from a jar, drain and mash them thoroughly with a fork.

Add the mashed chestnuts to a large bowl, and combine with the salt and chestnut flour. Mix until there are no lumps.

Gradually add the water until the dough is homogeneous. It should remain a little bit thick.

Divide the dough into eight balls, each the size of a golf ball.

Take two sheets of parchment paper. Lightly flour the surface of one with chestnut flour, and place a ball of dough in the middle. Flour the surface of the ball and cover with the other sheet of parchment paper. Flatten the ball to form a circle and roll the matzah out. You can use a cookie cutter if you want them to be perfectly round.

Heat a nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Remove the top parchment sheet and flip the bottom sheet over to lay the uncooked matzah into the skillet. Cook it for 30 seconds, flip it, and cook for another 30 seconds. Let the matzahs cool on a cooling rack to ensure they remain crispy.

LILA BALTAXE, a Boston University senior and contributing writer, contributed to this article.

This story appeared as an Online Exclusive in April 2025.